This is the seventh post in a series entitled, “A Potter’s Journey” for American Craft Council’s website. This post tells the story of growing my pottery businesss with the help of a mutually beneficial partnership with a local coffee shop, the Local Blend:

American Craft Council, “A Potter’s Journey: Launching a Pottery Business Venture and Fighting to Keep it Alive”

This is the fifth post in a series entitled, “A Potter’s Journey” for American Craft Council’s website. This post tells the story of launching my pottery business venture immediately after college graduation, as well as the trials and tribulations that I overcame during the first 3 years of business:

“A Potter’s Journey: Launching a Pottery Business Venture and Fighting to Keep it Alive”

Check back for my newest pottery, available in my online store December 1st:

Cosmic Pots: The “Goldilocks Glaze”

Thirty-four years ago, astronomer and Cosmos host Carl Sagan made his famous claim:

“If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.” – Carl Sagan. “The Lives of the Stars.” Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. PBS. 1980.

Sagan could have been talking about making anything from scratch. His goal was to convey that everything on earth, everything in the universe, is made up of precise combinations of the most basic elements, and those elements were created in stars’ nuclear cores. We could also say, “If you wish to make a pot from scratch, you must first invent the universe.”

These star-forged elements combine to form all the components of ceramics: the different strains of clay (silicon and iron), the water used in throwing (oxygen and hydrogen), the arboreal ingredients of glazes (calcium), and even the potter himself (carbon). Entire books could be written focusing solely on one of these ceramic elements.

Copper, for example. Copper red glazes have been meticulously pursued and produced since the fifteenth century in China. The new host of Cosmos, Neil deGrasse Tyson, often analyzes the concept of a “Goldilocks planet” – a planet which has the precise conditions for possibly sustaining life. A successful copper red glaze is a “Goldilocks glaze.” Everything in both the recipe and the firing must be perfect.

Copper, for example. Copper red glazes have been meticulously pursued and produced since the fifteenth century in China. The new host of Cosmos, Neil deGrasse Tyson, often analyzes the concept of a “Goldilocks planet” – a planet which has the precise conditions for possibly sustaining life. A successful copper red glaze is a “Goldilocks glaze.” Everything in both the recipe and the firing must be perfect.

As Sagan and Tyson have taught us, science is found in everything we do. Baking an apple pie from scratch, developing a new drug, and mixing and firing glazes all rely on experimentation, creativity, and chemical reactions. A potter doesn’t need a degree in chemistry, but he uses some pretty cool science to produce copper red glazes.

Nowadays, gas-fired kilns produce the best conditions for copper red glazes, but ancient Chinese potters created their beautiful pieces using only wood-fired kilns. Many potters do not have regular access to gas- or wood-fired kilns, and use electric ones instead. Electric kilns eliminate the need for constant temperature monitoring, but they are unable to create the atmosphere copper red glazes require.

Nowadays, gas-fired kilns produce the best conditions for copper red glazes, but ancient Chinese potters created their beautiful pieces using only wood-fired kilns. Many potters do not have regular access to gas- or wood-fired kilns, and use electric ones instead. Electric kilns eliminate the need for constant temperature monitoring, but they are unable to create the atmosphere copper red glazes require.

Copper red glazes need to be fired to a temperature called “cone 10.” This photo shows three cones (small pieces of clay), set up inside a gas-fired kiln. Each of these pieces is made from a different factory-produced type of clay formulated to melt at a certain temperature. A device called a pyrometer can be used to measure the temperature of the air inside the kiln, but what really matters is the temperature of the clay, hence the use of cones. When cone 10 melts, the potter knows the clay is roughly 2345 °F.

Even inside the same kiln, the atmosphere unavoidably varies. The pots below all had the same glaze and firing, but were placed in different areas of the kiln.

Even inside the same kiln, the atmosphere unavoidably varies. The pots below all had the same glaze and firing, but were placed in different areas of the kiln.

The green color on the right also occurs when firing a copper glaze in an electric kiln.

The green color on the right also occurs when firing a copper glaze in an electric kiln.

Color, just like copper, depends on the stars. Light from our sun strikes objects on earth, and those objects absorb some wavelengths of light and reflect others. The wavelengths they reflect are the colors we see. As Tyson puts it:

“Color is the way our eyes perceive how energetic light waves are.” – Neil Degrasse Tyson. “Hiding in the Light.” Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey. Fox. 2014.

Thankfully, potters did not have to create the universe to make pots from scratch. Their ingredients are already present in the cosmos, swirling in the air and lurking in the earth, waiting for them.

Glaze Chemistry and Alchemy

The New World Dictionary, Copyright 1967

In many ways, the work of the modern potter mirrors the work of the ancient alchemist. Potters blend earthly materials like clay, stone, and ash, into complicated glaze mixtures. Then through fire, these base substances transform into precious works of art. With glaze chemistry, and one part modern alchemy, potters turn the natural elements we once took for granted into the treasured artifacts we display in our homes and galleries.

It’s interesting to see how much the glazing, alchemy, and human life relate to each other. Bernard Leach, author of A Potter’s Book, helps us understand glazes by relating them to the body. He says most glazes have 3 main parts -the blood, bone, and flesh. Here’s how they work:

1.) Fluxing agent or “life blood of the glaze” – causes the glaze materials to melt and flow together in the kiln firing.

2.) Refractory or “bone of the glaze” – resists heat and melting, providing structure and strength to the glaze body.

3.) Glass Former or “flesh of the glaze” – creates complexity, depth and unique qualities.

(page 133-134)

Similar to Bernard Leach, the early alchemists fused their chemical efforts with the body. Calling their experiments the Magnum Opus, or “Great Work,” these men searched tirelessly for the right chemical concoctions that would enrich life or prevent death. In some ways, full-time potters do the same through glaze chemistry. They are constantly searching for that perfect potion that will immortalize a clay body and turn sand, water, and ash into gold.

These 2 books, by potters John Britt and Phil Rogers, gave Joel the necessary skills to develop that perfect glaze surface, but like the early alchemists, he’s still searching.

Like alchemy, glazing is often a fiery, messy, and sometimes toxic process. The kiln releases CO2, the powdered glaze materials are dangerous inhalants, and the heavy metal colorants cause skin irritation. Joel mixes all his glazing in an old boat shed. This dirty, dark laboratory gives him 24 hour access to glaze experimentation, providing the perfect amount of chaos to create beautiful works.

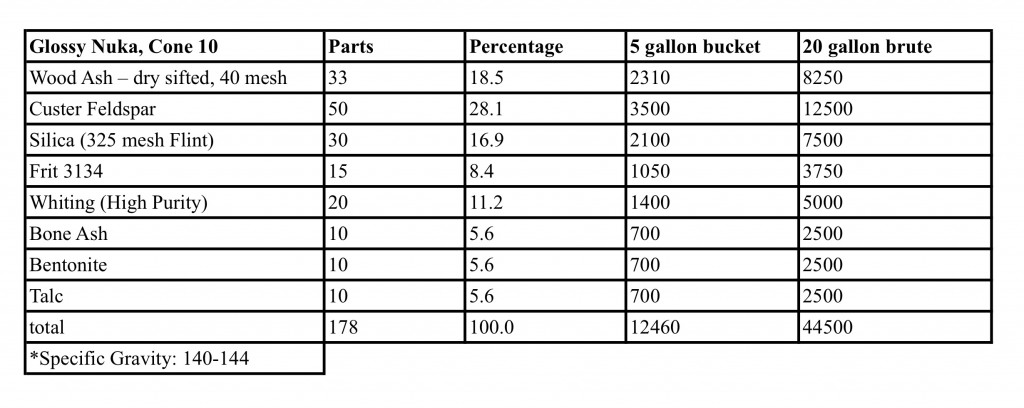

Joel’s pottery has to be strong enough to be used in a coffee shop everyday. The Local Blend Baristas say they wash a mug up to 5 times per day, 7 days per week! With this in mind, Joel adapted the Nuka glaze to suit the stress. Traditionally a simple 3-ingredient mixture, Joel added more chemicals to strengthen the glaze surface, reducing flaws like pinholes and crazing while increasing durability and gloss. Here’s the recipe for all the curious potters out there:

Some potters spend their careers trying to find the right glaze mixtures. In next Friday’s post, we’ll delve into some of these mixtures more and explore the lure of pretty blue pottery.

“At my St. Ives workshop each summer we are asked by three visitors out of four for colour and yet more colour, blue and the more intense the better, is easily the favourite.”

– A Potter’s Book, Bernard Leach, page 36

Finding a Balance in an Imbalanced Art World

Hannah Anderson worked as a “Pottery Marketing Intern” this semester. She is a senior Art major at the College of St. Benedict/St. John’s University. In this post, she describes our semester long task of trying to define the role of pottery in the contemporary art world.

Guest Posting by Hannah Anderson (view her Linkedin page here)

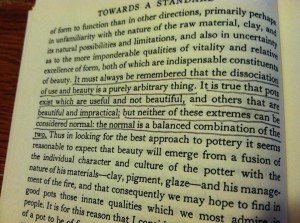

Throughout my internship with Joel, we had many discussions of “high art” vs. “low art” and where his pottery fit into the mix. High art, one could argue, is not functional for the consumer. Traditionally, the function for this type of art is to sit in a museum as a masterpiece, observed through this elevated status. Low art is generally mass-produced, inexpensive, and far more available to the public. In my critical theory class, we discussed how museums have opinions on high and low art as well, and can influence how people view artwork by either appearing intimidating or more approachable.

The terms “high” and “low” art should be reevaluated and adapted to today’s contemporary art world. Words that correlate with high art seem far too Renaissance or Baroque in feel, such as “master of art,” prestige, traditional, western, still-life, landscapes, portraits, and, my favorite, original. This particular word poses the question: can high art even exist anymore? I would argue that it certainly still exists, but not in the same light in which it was originally established. High art and low art should be adaptable terms for each new generation of artists. Low art has synonyms such as: consumerism, production, affordable, advertised, ordinary, etc. This is a challenge many artists face today, and it creates a huge imbalance in the art world.

Joel poses the question, “why are we making and selling pots?” He gathers a lot of insight from potter Warren Mackenzie, whom also has a lot to say about art as a functional vessel vs. sitting in a gallery space. Warren is an 89 year old, world-renowned artist. He is most at ease with his work when he knows it is being used, handled everyday and looked at often. Pottery has the potential to be the most intimate of artwork, because it’s users have constant contact with it. Clay is not expensive and is made from the earth, so when does it make the transition from low to high art?

Price plays a factor into what is high and low art. Warren says “A 10 dollar pot, now that’s affordable.” He says that if it breaks, then it is not a huge loss. This is interesting coming from a renowned artist, because his philosophy conflicts with his position in the art world; his pots resell on Ebay.com for hundreds of dollars everyday. Mackenzie says, “Unfortunately, now I only sell through galleries.” His philosophy seems more focused on low art, but his standing is high.

I like to think that many artists in today’s art world present a mix of high and low art, and it is perhaps just difficult to find the balance. Right now, an imbalance is evident in Joel’s artwork. His pottery is functional, consumer-friendly, priced lower than most professional potters, and is meant to bring a comfortable aesthetic to anyone’s home. His online store is in contrast with this idea, because we take a high art approach by using professional photography equipment to shoot pots in front of a gradated background. We then use these photos to try and join the contemporary art world.

I wonder, is the Local Blend pottery high or low art? At the Local Blend coffee shop, they use Joel’s pottery in mass, so anyone can eat and drink from his pottery everyday. This seems much closer to low art to me. We take the same pots and put them in front of a gradated background, making them high art in a different atmosphere. Without a little low art, high art wouldn’t be possible, since the Blend is where most of Joel’s income is generated. Writing about this venue has also brought him some of his biggest successes in the art world, including 2 major magazine publications. Perhaps these everyday pots will someday be elevated to a high art status?

Low art is what’s paying the bills, yet in the future, Joel wants to support his livelihood with a balance between low and high art. This means more of his income needs to be generated from our work on the online store. One way we accomplished this was by branding his artwork in a more focused way, using one glaze: the Nuka Glaze with iron. Nuka with iron had a great deal of success for Joel throughout my internship, enough for him to narrow his focus toward solely that glaze. Currently the online store has less Nuka with Iron than Joel would like, and his future plans are to recreate his online store geared toward pottery of only that glaze type. Over 50% of the online sales were Nuka with iron, and Joel sold pots with this glaze type to five different people both locally and nationally in one week. He has also completed 4 dinnerware sets in this glaze, 2 of which were sold through wedding registries. We see huge potential in this glaze combination.

This branding was influenced by Ayumi Horie, who certainly has a recognized, established, successful brand for herself. Her style is easily recognizable on every pot. Her artwork sells at high prices online and is always sold out in less than a day. Moreover, Horie has earned her place in the art world through years of consistent craftsmanship, a huge resume, and skillfully writing about her craft in major publications.

Our experience with high art continued through Paige Dansinger– an internationally renowned painter and art historian who is collaborating with Joel. She makes high art in the form of painting on canvas, digital paintings on IPads, projections, performance, and most recently, painting with glazes on Joel’s pottery. During my internship, she opened a gallery in the Minneapolis Skyway Mall called Gallery Paige. Everyday, she exhibits and sells her artwork as high art. The collaborative work made by herself and Joel has huge potential to take off in the high art world.

To conclude, perhaps in today’s world, the balance needs to be found in the middle of the spectrum between high art and low art. Are the best artists those who spend their time making both high and low art? One could argue that they can reach the most amount of people that way. Because that in fact is what art is all about: reaching the most amount of people with a particular message. The meaning of art and its purpose to be seen can easily get lost when identifying it as either high or low. As renowned potter Bernard Leach said, “To me the greatest thing is to live beauty in our daily life and to crowd every moment with things of beauty. It is then, and then only, that the art of the people as a whole is endowed with its richest significance.”