Anyone who’s flown with a commercial airline before knows the dread that accompanies handing off your luggage to the disgruntled employee who chucks your bag onto the conveyer belt without blinking. A similar leap of faith occurs with online shopping, when you enter your credit card number and simply trust that the product will arrive safely and soon.

Joel’s pottery is pretty tough. His mugs survive being washed and handled tens of times a day at the Local Blend. I won’t disclose how often my own Cherrico pottery cups get yanked out of the cupboard to be filled with wine and clanked down onto a coaster. Joel himself has no qualms piling up pots for one of his signature #potsonpots moments.

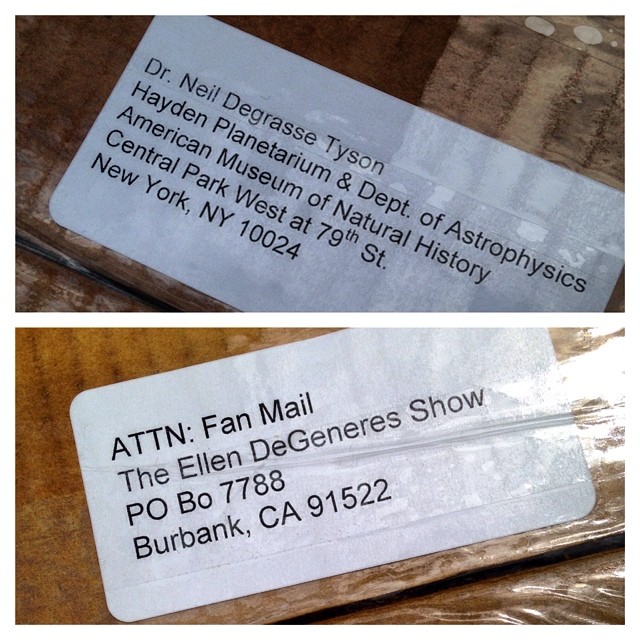

But that airport bag woman, that USPS postman, they just don’t care. One of my intern duties is prepping the pots sold online for their journey through this uncaring world. The last thing Joel wants is for a customer – be it a mother in Iowa or a celebrity like Ellen Degeneres – to open that package and find a broken pot. Not only does this make for poor customer service, but it also wastes time and money because a new pot must now be packed and shipped free of charge.

Another way Joel saves money in the shipping process is by following his blunt philosophy of: “I hate buying things.” Thankfully the unavoidable exceptions to this rule (tape, labels, a box cutter, etc.) are relatively cheap. Other materials he can find completely free.

The first step of shipping a pot is wrapping it in newspaper. We use regular old newspapers (free!) or a large roll of blank newsprint Joel got from a friend who works for a local paper (also free!). The last step of shipping a pot is putting it in the box. As many frequently-moving college students know, liquor boxes are a must-have. They’re plentiful, a convenient size, sturdy, and – say it with me now – free. The downside to using liquor boxes is they must be turned inside out because it is illegal for regular folks like us to ship in liquor boxes.

What about the middle step? Besides frugality, Joel also pursues sustainability in the packing process – in the form of hundreds of egg cartons.

A few years ago, Joel connected with a local farmer named Everett. Everett had a deal with the recycling center to take the egg cartons they received. (Brief PSA: Even though many of them are made from post-consumer materials, egg cartons are not recyclable. Huh. Who knew?) As a chicken farmer, Everett used some of the cartons himself, but the rest he kept in his garage in massive stacks, knowing someone would have a use for them one day.

Joel was that someone. Egg cartons are made to transport a product much more fragile than his pottery. They provide great cushioning and quickly fill up the box’s empty space without adding very much weight, which is paramount when paying for postage. Plus, two van loads of egg cartons cost Joel only one box of pots for Everett.

Mutual sustainable practices such as this are not new to our community. When Richard Bresnahan was founding the St. John’s Pottery, he was drawn to the economical habits of the monastery, especially the carpenters:

“He discovered they rarely threw anything away and carefully salvaged doors, windows, paneling, fixtures, and other hardware when structures were razed or remodeled. In the hands of Benedictine carpenters, such discards were given new life.” – Matthew Welch. Body of Clay, Soul of Fire. St. John’s University Press, 2001. Page 52.

Let’s say you decide to purchase a pot from Joel’s online store. (Maybe you entered his Shark Tank Pottery Cup Giveaway, and you wanted to give your anticipated prize cup a companion.)

I receive your order confirmation and find the corresponding pot. Inside a box which once protected bottles of Jameson, I build a nest of Everett’s egg cartons. The newspaper-wrapped pot gets snugly squeezed in and is topped off by more cartons.

Finally, I close the lid, without taping it for now, and shake that box like I’m a USPS delivery woman chucking it onto your doorstep because it’s the middle of January and it’s 40 below and I want to get back into my truck ASAP. If I don’t feel anything moving in there, I’ve done my job right. All the package needs now is tape, labels, and a lift to the post office.

A few days later, you’ll get to open that box and see your trust in online shopping fulfilled.